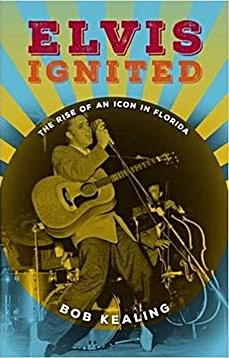

Back in 1956 a young Elvis Presley was booted out of West Palm Beach bar. It was one afternoon in 1956 and Elvis ambled into Dude Dodge’s Marine Show Bar for a drink. Seeing a young punk with jet-black greaser’s hair the bar keeper didn’t believe this pretty boy was 21 and so the future Rock'n'Roll king was ejected from the saloon. It’s one of many intriguing anecdotes in Bob Kealing’s new book, “Elvis Ignited: The Rise Of An Icon In Florida”. The author and longtime TV journalist connects a lot of previously unconnected dots, showing how the Sunshine State was an incubator for Presley’s breakout year of 1956.

Kealing makes a persuasive argument that Presley’s “moonshot” to fame could not have happened without Florida, from his uneasy relationship with manager and former dogcatcher Col. Tom Parker to meeting Mae Axton, who in one afternoon at her Jacksonville home would help write the song that made Presley a nationwide sensation “Heartbreak Hotel.” “There’s a rich tapestry of Elvis in Florida” said Kealing, “I don’t think it was any accident that kids started picking up guitars and forming garage bands after seeing him. He was the template of cool in Florida.”

On Feb. 20, 1956, Presley performed four shows at the Palms Theatre on the corner of Clematis Street and Narcissus Avenue. It was his first headlining show in a theater, topping a country-leaning bill that included the Carter Sisters, Louvin Brothers and the Blue Moon Boys, who were Presley’s backup band: guitarist Scotty Moore and bassist Bill Black. By the way, that bartender wasn’t the only one who missed Presley’s significance in West Palm. Even with ads in the paper hyping his show, The Palm Beach Post didn’t bother to cover it, despite massive crowds of teenagers and screaming that practically drowned out Presley’s singing.

Kealing cuts the paper some slack. “He played West Palm Beach as a headliner in name only,” he said. “He’s just recorded ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ but it hasn’t come out yet. He’s on the cusp of fame in West Palm Beach.” “Elvis Ignited” pulls together many fascinating strands of the Presley legend. He first saw the Atlantic Ocean in Daytona Beach. The iconic photo from his first RCA album was shot at a Florida concert. “Heartbreak Hotel” was inspired by an account of a suicide note — “I walk a lonely street” — in the Miami Herald. Presley, who made $50 at his first Florida gig, even opened shows here for a pre-TV comic named Andy Griffith.

And the growing, unhinged passion he stirred in Florida teenagers — and the fear it stirred in parents — reached its apex when a Jacksonville judge pondered whether his pelvis-wiggling was grounds for an obscenity charge. (Presley waggled his finger instead.)

Male newspaper reporters in 1956 sounded like hysterical prudes writing about Presley concerts, the Miami News’ Damon Runyon Jr. described him as having “the glassy gape of a hypnotized hillbilly.” But one thing Kealing’s book celebrates are unsung female journalists in Lakeland, St. Petersburg, Miami and Orlando who were able to see Presley with more clarity and insight. “Men wrote in the point-of-view of parents,” Kealing said. “But thank goodness you had these prescient women. They got to know the real person behind the persona.”

Of course, in those days, celebrities were more accessible. Anybody who wandered backstage could find a shirtless Presley willing to give a female fan a smooch or a reporter an interview. (And female reporters inevitably got a hug and a kiss, too.) Before his fame became so overwhelming, this Elvis would flirt with waitresses at truck stops or talk to fans at roadside motels. Kealing’s book deftly captures a pre-Interstate Florida where an anonymous Presley would be traveling for grueling hours down every two-laner in the state in his signature automobile. “He’s on Tamiami Trail, he’s on 441, he’s on U.S. 1, he’s driving the pink Cadillac,” said Kealing.

It’s one of the reasons Kealing loves writing about that era in Florida: It could give visitors a sense of how Florida fans were pioneers in the cult of Elvis. “Floridians had extraordinary access to Presley early on,” Kealing said. “Imagine what it must have been like for these kids to see him in their black-and-white world, whirling onto the stage in Technicolor.”