It has been thirty-two years since Elvis Presley died at age 42, a bloated victim of prescription pills and Nutter Butters, and over fifty when a thinner Elvis burst onto the American scene, singing and twitching his way into the hearts of millions. Although it seemed he reigned as The King for as long as Victoria ruled England, his career lasted a mere twenty years, including a stint in the army and a career lull from which he came back in a celebrated TV special. Yet he remains a cultural lodestone today.

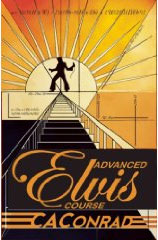

Elvis inhabits the psyche of poet CaConrad, author of Advanced Elvis Course, an odd compendium of poems, dialogues, quotations, dreams and anecdotes. The first half describes the poet’s pilgrimage to Graceland, Mecca for Elvis fans, consisting of a gauche plantation-style mansion and museum complex. Graceland essentially serves as a house of worship to visitors like Conrad, a place to experience Elvis’s mystical effect. Throughout the book the author quasi-Biblically capitalizes pronouns referring to Elvis: “Say His name, hold onto your dream, and be healed.” Conversely, in a dialogue with a fanatical Christian, he spells “God” with a small “g,” diminishing organized religion beside the Elvis phenomenon.

Incidents from Elvis’s life, a tour of his private jet, reflections on his movies, excerpts from Priscilla Presley’s memoir, and, more seriously, a visit to Meditation Garden, his burial site, spawn poems that contemplate Elvis’s multiple dimensions. Many dwell, unsurprisingly, on Elvis’s sex appeal. In “More than Anything,” Conrad wishes he could obtain permission from Lisa Marie Presley to “spend one night in His bedroom, next to His bed, naked, dressed in a body condom, imagining I’m his happy little sperm … blissfully shot from His hardened, kingly shaft.”

Conrad acknowledges the heavy kitsch enveloping Graceland, but he refuses to condemn it--he understands it goes with the territory: “The array of Elvis coffee mugs in the gift shop are wonderful on the eyes.” Later, he attends a Delacroix exhibition and observes in the museum store Delacroix t-shirts, postcards, jigsaw puzzles, hats and – yes – coffee mugs bought by two yuppies who frown on his Elvis t-shirt. “They’re fools really. They think this gift shop is any different from Graceland.” With this statement he welcomingly punctures the pretentions of snobby art patrons who engage in the same vulgar schemes perfected by the Presley Estate.

The book’s second half is set in Philadelphia, where back at home Conrad experiences the lingering effects of his Graceland trip. Several times he compares Elvis to Philadelphia’s most renowned resident, Ben Franklin, another creative genius. He judges lovers by their resemblance to Elvis, not physically, but in their underlying sexual energy. Of his boyfriend he writes, “The reason my relationship with Norberto has lasted as long as it has is due to the enormous number of attributes of Elvis he has absorbed.” Post-Graceland, Conrad comes off as Elvis-obsessed to several acquaintances. Exclaims Norberto, “Why do you always bring him up? So annoying!”

One of my favorite pieces in the book involves a flyer Conrad posted around Philadelphia containing a phone number where one could leave a message for Elvis. He publishes fifteen of them, ranging from a message left by “Prozac Poster Girl,” who assures Elvis, “if they had Prozac back in your time it could’ve helped you” to another person scolding, “Elvis is dead! Get a f*cking life!” to a bereaved daughter movingly describing her mother’s final days when they reminisced about attending Elvis’s last show in Philadelphia: “It gave her strength. It gives me strength too.”

Elvis Presley is such an icon because of the many interpretations to which he has been subject. He is so entangled in history and myth that he has become virtually unknowable. On one hand, he was a pioneering rock and roll singer; on the other, he was a gifted gospel singer and by all accounts a believer. He was a symbol of sin to his contemporaries for the way he shook his hips when singing, but today’s hip-hop artists regularly grab their crotches while they perform much more suggestive songs than he ever imagined. He began his career as a rebel stirring up America’s youth, but he ended it as a Las Vegas lounge singer, crooning for the middle-aged masses. In short, Elvis is largely a blank screen onto which legions of fans, music critics and academicians have projected their beliefs.

Conrad intuits this fact completely, and, like these other Elvis watchers, he interprets Elvis in his own way. The book’s strength lies in how Conrad addresses larger socio-cultural issues surrounding Elvis through personal encounters with the man’s songs, history, residence and, not least, fan reaction. Conrad’s genre-defying book is a biography of sorts, telling the story of a simple but supremely talented Mississippi boy who left behind a complicated legacy that curiously endures in his followers’ collective memory.